Last week I blogged about the curriculum I created for young musicians at Trinity Laban conservatoire. This week, I’ve been collating their reflections on their last year’s study of the the Alexander Technique with me.

The young people I work with range from 11 to 19 years old. It’s always fascinating to see these students’ very individual responses to the Technique, and so heartening to see what a difference it has made in their lives.

Below are four of around twenty responses I have had this year, some of which demonstrate a maturity beyond their years.

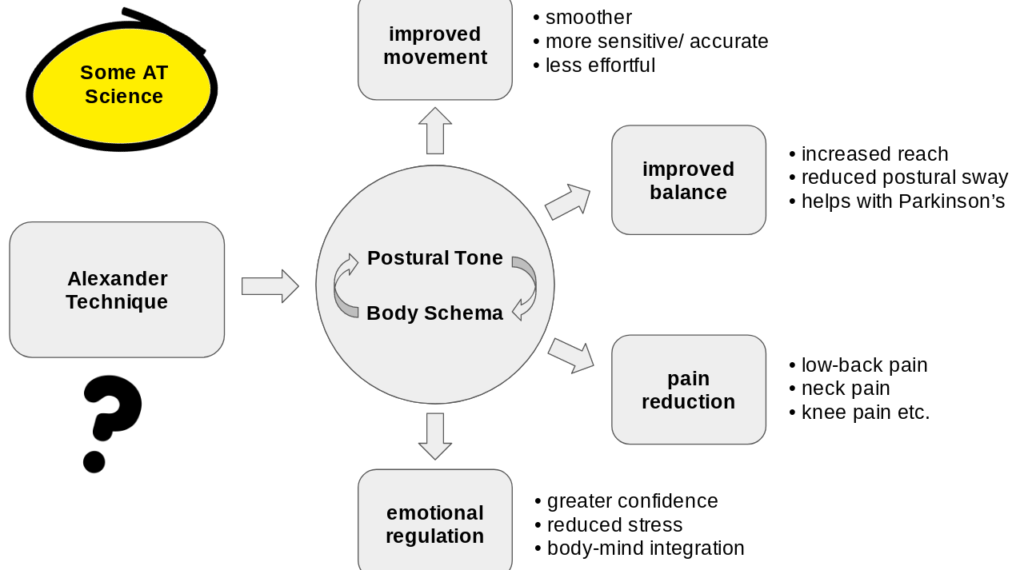

For me, Alexander Technique is the awareness of our body and our behaviours. It helps us to be aware of the spaces that surround us and the people and events that influence us. It could be defined as the practical study of being, where we reflect on us and come back to ourselves.

Maya (15)

It helps me ground myself and take the necessary time to do things, however minor they are. It brings clarity into my life. It helps me to look after my physical well-being, which feeds into my mental well-being. The thing that most resonated with me was the concept of end-gaining and how to make the most of doing something rather than ‘getting it done’. It also helps me with preventing injury and anxiety. It also helps with preventing unhealthy physical responses to injury, for example dropping something and lurching to pick it up.

Mimi (16)

The idea that there is no right or wrong way to be. We are habitual beings and we can sometimes be cruel to ourselves and expect ourselves to do more than we need; for example, when we practise we decide that we won’t make any mistakes but then when we do we beat ourselves up about it. Alexander technique for me is being kinder to yourself and allowing freedom in your mind and body by creating space. The way we react to different happenings in our lives affects our posture and tension in our muscles. Sometimes the best thing to do when I practise is to just play the whole piece through without reacting to my mistakes. I know I have got into the habit of pulling faces and stopping if I make a mistake but in the long run when I perform this piece I need to just carry on regardless. Alexander Technique has allowed me to learn to just observe my annoyance or anger and accept it and move on. Another BIG part of the technique is pausing, just taking a moment and checking in with yourself and your freedoms. Am I breathing, is my neck free, are my feet spreading? It’s an awareness of your environment and paying attention, living in the now rather than worrying about the past and the future. It’s making life simpler and easier, being kind to yourself. 🙂

Rose (15)

For me the Alexander Technique is a way of me being more in tune with my body which in turn helps my interpretations to breath and sing more; I have felt for a while that there is a disconnect between my imagination and my body when it comes to playing music, almost as if there is a thick mist in between my mind and body which hugely affects the way I sound. This is slowly beginning to improve as I become more aware of my body and surroundings. It also allows me to enjoy playing more too as it is physically more comfortable and helps me to feel more natural and relaxed when thinking about emptiness in my body. I also have found it useful in other aspects of my life; in the past I have had a tendency to hunch over lots and ‘shrink’ in the face of social situations in particular. I still need to work on it but thinking about the head going up and away for example has really helped with my confidence. The idea of ‘end-gaining’ has also proved useful in school when comparing grades etc to my friends or when doing competitive things! I feel AT is definitely helping and I look forward to continuing with it.

Tom (17)