Introduction

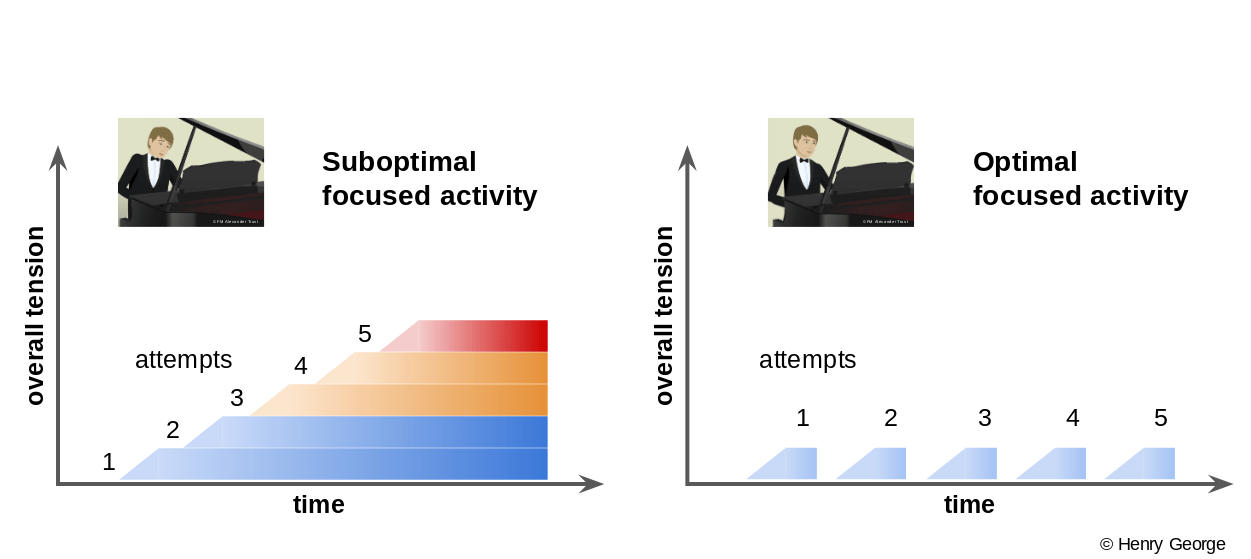

FM Alexander formulated a unique approach for dealing with the way habit interferes with human potential. Speaking well on stage was Alexander’s own preoccupation, but the approach can be applied to any activity, or ‘end’. Examples range from ‘simple’ actions such as standing up from a chair or typing at a laptop, to complex activities such as playing a musical instrument or sports.

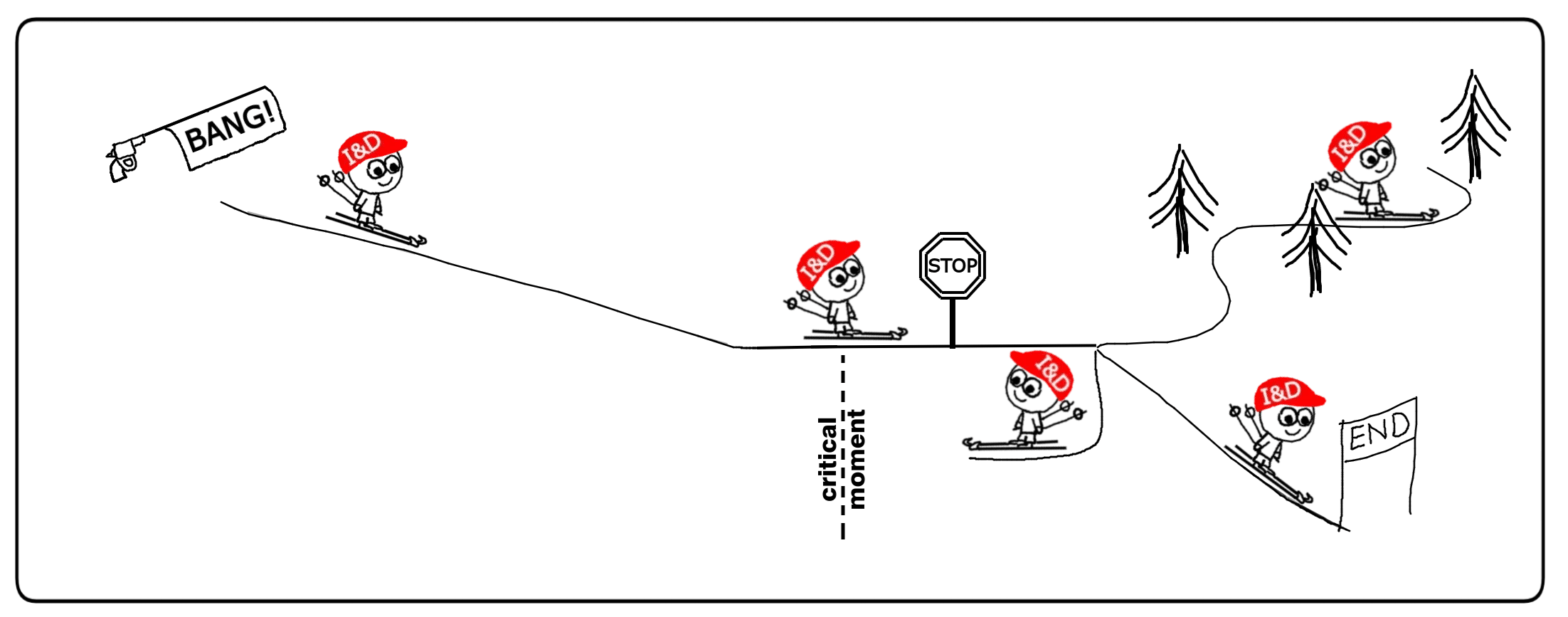

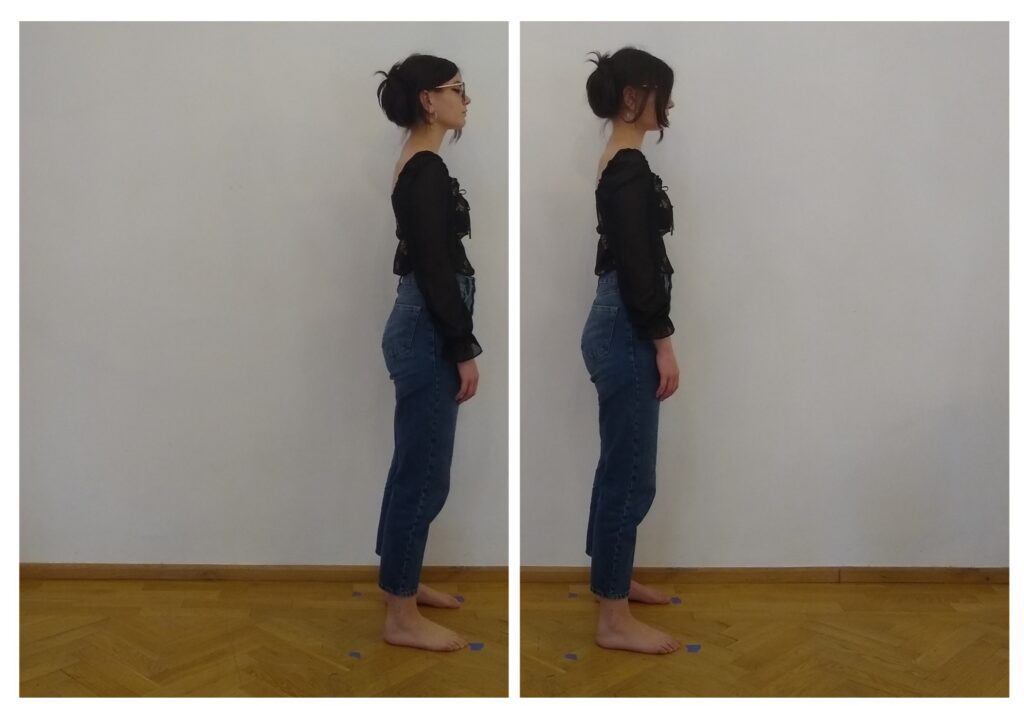

I’ve used the analogy of a skier to create a fun visual guide to Alexander’s approach (sneak preview below). I also want this to be a practical guide, and so I’ve included a detailed example of a singer using this approach to improve an aspect of her performance (all sorts of other examples could have been used instead).

A final point: you’ll need an understanding of the Alexandrian principles of Inhibition and Direction, but these are explained (with an appropriate link) in the text.

‘I see and approve the better, but follow the worse’

The English writer and philosopher Aldous Huxley had lessons with FM Alexander, and it influenced his life and writings in various ways. In his novel Eyeless in Gaza (1936), there is a character called Miller, based on Alexander himself, who teaches ‘a technique for translating good intentions into acts, for being sure of doing what one knows one ought to do’. In the novel, Huxley presents the technique as a solution to the ‘video meliora proboque; deteriora sequor problem’: a quote from Ovid meaning ‘I see and approve the better, but follow the worse’.

It is precisely this problem which FM Alexander sought to overcome in relation to muscle tension he’d built up around speaking. No matter what he did, he found that he couldn’t prevent ingrained habits interfering with the use of his voice, to such an extent that his career as an actor was in jeopardy. Despite his best intentions, even the thought of speaking on stage would lead to tension and hoarseness.

Alexander describes these investigations in his book, The Use of the Self (1932). And it is here, over four pages, that he describes his plan for outwitting any habit of muscular tension which gets in the way of what we want to do.

I have included Alexander’s own words in an appendix (below), but the point of this article is to explain his ingenious process as a visual guide. The complete illustration is below (or click for A4 pdf), and I have added an examination of its four sections below that.

Enjoy!

1. The grip of habit

In The Use of the Self, FM Alexander writes that ‘Human activity is primarily a process of reacting unceasingly to stimuli received from within or without the self’.

In this case, our skier in the illustration receives a stimulus from outside the self (the ‘bang!’) to gain a particular end. However, their reaction to the stimulus involves anxiety, muscle tension and a lack of control, and so they inevitably do not achieve their end satisfactorily and instead tumble past it. Habitual reactions have taken over, and the skier is thwarted.

Example

Minnie is a soprano who wants to improve her singing at the top of her range. She sets herself the goal of singing a beautiful top C (a stimulus received from ‘within the self’), but each time she tries, her desire to ‘get it right’ brings about anxiety and muscular tension. The result of her attempts are an unpredictable, strained and unsatisfactory quality of sound.

2. Partial success

The skier has been working with the principles of the Alexander Technique. When they receive the stimulus to act this time (the ‘bang!’) they are able to inhibit their habitual reaction to it, and direct the overall quality of their coordination, or use. This process is represented by the ‘I&D’ printed on their red cap (anyone not yet familiar with inhibition and direction can read a great summary here).

However, at the ‘critical moment’ when the skier goes on to attempt to gain their end, they revert to their wrong habitual use and fail in their attempt.

Example

Minnie has been practising her singing by lying down on her back in the semi-supine position. She gives herself the aim of singing a top C – in other words, a stimulus from within the self. Lying on her back helps her notice some muscle tension building as a reaction to the stimulus to sing – in particular, she notices herself arching her back and compressing her neck. She works with inhibition and direction to reduce unnecessary tension in the face of the stimulus to sing. Everything goes well until the critical moment when she opens her mouth to release the note, at which point she reverts to her habitual use and fails in her attempt to sing her top C freely and with ease.

3. Outwitting habit

The skier has deepened their practice. As before, they begin with an overall plan to gain their end but don’t react immediately to the stimulus to do so (the ‘bang!’). Instead, they continue to inhibit and direct. Further, at the critical moment when they might have gone on to gain their end, they stop and reconsider. In doing so, they realise that they actually have three options: to gain their original end, do nothing at all, or do something entirely different such as ski along a forest trail. They then make a fresh decision to do one of the three, making sure that they continue to inhibit and direct, no matter which option they choose.

It is important to note that, by inviting choice at the critical moment, the power of the end to bring about habitual tension is diminished. By saying to themselves, ‘perhaps I won’t gain my end, and perhaps I will’ – and by inhibiting and directing no matter the choice they make – it becomes possible for the skier to outwit the habit which dictates that tension must always accompany their desire to gain their end.

In other words, inhibition and direction must continue throughout the process, regardless of stimuli or critical moments!

Example

Minnie is lying down again to practise her singing; this position helps her spot habitual tension more easily because overall her muscles are working less. As before, she begins with an overall aim to sing a top C. She notices any instinctive reaction to the idea of singing a high note, and successfully inhibits it. She then mentally projects directions through her whole self to improve her overall coordination. And this time, at the critical moment when she opens her mouth to sing, she stops. She makes a fresh decision either to a) sing the top C; b) do nothing at all or c) raise her hand, and continues to inhibit and direct while following through on one of the three options.

4. Habit defeated

With practice, the skier is able to not react with tension when gaining their end. They have broken the link between the gaining of an end and the habitual tension that previously accompanied it. Unnecessary tension is the enemy of the effective performance of any task, and so any steps which can be taken towards releasing habitual tension will increase the likelihood of achieving an end successfully. This is illustrated by the skier going on to cross the finish line without tension.

Freeing oneself from the habits of unnecessary tension is indeed therefore a solution to the problem identified by Aldous Huxley and referenced in my introduction: video meliora proboque; deteriora sequor, or ‘I see and approve the better, but follow the worse’. Alexander concludes:

After I had worked on this plan for a considerable time, I became free from my tendency to revert to my wrong habitual use in reciting, and the marked effect of this upon my functioning convinced me that I was at last on the right track, for once free from this tendency, I also became free from the throat and vocal trouble and from the respiratory and nasal difficulties with which I had been beset from birth.

FM Alexander (1932) The Use of the Self . Reprint. London: Gollancz, 1985. pp.47-48

Example

With practice, Minnie is able to formulate her plan to sing a top C without unnecessary tension. Moreover, through pausing and giving herself choices at the critical moment of opening her mouth to sing, over time she dissolves the tension that had become habitually associated with the gaining of her end (singing a top C). Notwithstanding other limiting factors – such as physique, current health, technique or experience – she has become better able to reduce or eliminate an important factor interfering in her potential: the harm caused by habitual muscle tension.

Appendix: FM Alexander (1932) The Use of the Self . Reprint. London: Gollancz, 1985. pp.45-48.

After making many attempts to solve this problem and gaining experience which proved to be of great value and interest to me, I finally adopted the following plan.

Supposing that the ‘end’ I decided to work for was to speak a certain sentence, I would start in the same way as before and

(1) inhibit any immediate response to the stimulus to speak the sentence,

(2) project in their sequence the directions for the primary control which I had reasoned out as being best for the purpose of bringing about the new and improved use of myself in speaking, and

(3) continue to project these directions until I believed I was sufficiently au fait with them to employ them for the purpose of gaining my end and speaking the sentence.

At this moment, the moment that had always proved critical for me because it was then that I tended to revert to my wrong habitual use, I would change my usual procedure and

(4) while still continuing to project the directions for the new use I would stop and

consciously reconsider my first decision, and ask myself ‘Shall I after all go on to gain the end I have decided upon and speak the sentence? Or shall I not? Or shall I go on to gain some other end altogether?’ — and then and there make a fresh decision,

(5) either

not to gain my original end, in which case I would continue to project the directions for maintaining the new use and not go on to speak the sentence;

or

to change my end and do something different, say, lift my hand instead of speaking the sentence, in which case I would continue to project the directions for maintaining the new use to carry out this last decision and lift my hand;

or

to go on after all and gain my original end, in which case I would continue to project the directions for maintaining the new use to speak the sentence.

It will be seen that under this new plan the change in procedure came at the critical moment when hitherto, in going on to gain my end, I had so often reverted to instinctive misdirection and my wrong habitual use. I reasoned that if I stopped at that moment and then, without ceasing to project the directions for the new use, decided afresh to what end the new use should be employed, I should by this procedure be subjecting my instinctive processes of direction to an experience contrary to any experience in which they had hitherto been drilled. Up to that time the stimulus of a decision to gain a certain end had always resulted in the same habitual activity, involving the projection of the instinctive directions for the use which I habitually employed for the gaining of that end. By this new procedure, as long as the reasoned directions for the bringing about of new conditions of use were consciously maintained, the stimulus of a decision to gain a certain end would result in an activity differing from the old habitual activity, in that the old activity could not be controlled outside the gaining of a given end, whereas the new activity could be controlled for the gaining of any end that was consciously desired.

I would point out that this procedure is contrary, not only to any procedure in which our individual instinctive direction has been drilled, but contrary also to that in which man’s instinctive processes have been drilled continuously all through his evolutionary experience.

When I came to work on this plan, I found that this reasoning was borne out by experience. For by actually deciding, in the majority of cases, to maintain my new conditions of use either to gain some end other than the one originally decided upon, or simply to refuse to gain the original end, I obtained at last the concrete proof I was looking for, namely, that my instinctive response to the stimulus to gain my original end was not only inhibited at the start, but remained inhibited right

through, whilst my directions for the new use were being projected. And the experience I gained in maintaining the new manner of use while going on to gain some other end or refusing to gain my original end, helped me to maintain the new use on those occasions when I decided at the critical moment to go on after all and gain my original end and speak the sentence. This was further proof that I was becoming able to defeat any influence of that habitual wrong use in speaking to which my original decision to “speak the sentence” had been the stimulus, and that my conscious, reasoning direction was at last dominating the unreasoning, instinctive direction associated with my unsatisfactory habitual use of myself.

After I had worked on this plan for a considerable time, I became free from my tendency to revert to my wrong habitual use in reciting, and the marked effect of this upon my functioning convinced me that I was at last on the right track, for once free from this tendency, I also became free from the throat and vocal trouble and from the respiratory and nasal difficulties with which I had been beset from birth.